You are here

Time to Appreciate the Lowly Lichens

Time to Appreciate the Lowly Lichens

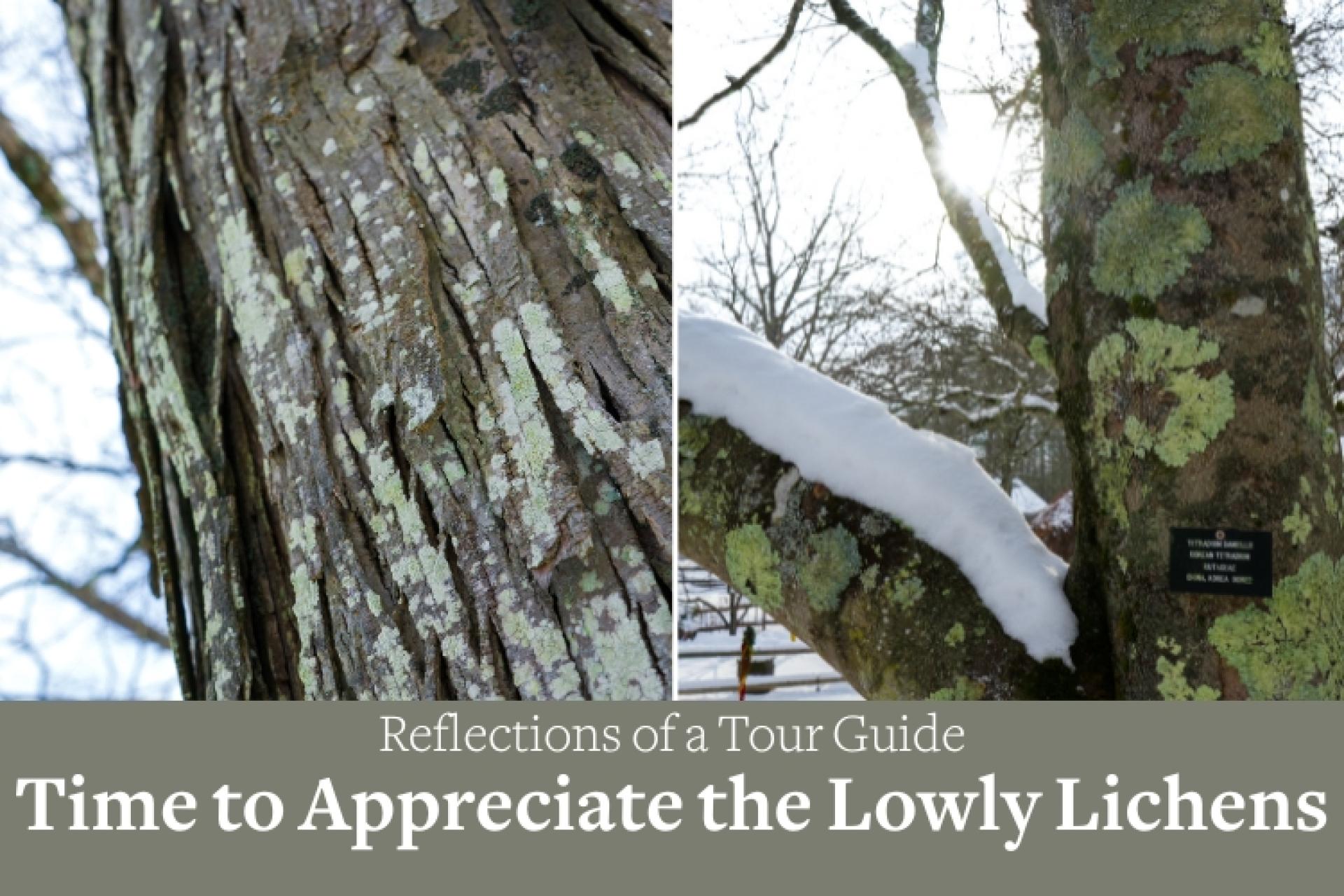

(Left) Beside the Education Center, a shagbark hickory (Carya ovata) hosts an intricate community of lichens, microbial partnerships etched into every fold of its remarkable bark. (Right) Lichens showcase their subtle beauty on a Korean evodia (Tetradium daniellii) beside our Visitor’s Center.

See how the lacy lichens have found purchase in the channels, sharing space in the hollows. Tree and lichen belong to one another.

— Margaret Renkl, “The Comfort of Crows”

by Chris Ferrero

A different landscape emerges once the last of our visitors have toured the gardens in the fall. After a typically spectacular fall finale, when Mother Nature strips away the last of the colorful leaves from trees, a more nuanced beauty is revealed.

This is the time of the year when new visual highlights take center stage, unfettered by the distractions of foliage, flowers, buds, and berries. The architecture of bare trunks and stem angles and woody burls reward the eye, as do contrasting bark textures and colors.

Rising to visual prominence is the complex mosaic of lichens on tree trunks, one of the most colorful and artistic features of the landscape of woody plants.

Even on our mid-summer BBG tours, when tree canopies are fully leafed out, visitors will comment on the lacy tapestries of lichens on trunks and low-slung branches of some of our prettiest specimens. We are sometimes asked what these decorative features are. And even if visitors have seen them before, they often voice a concern for the tree’s health. They frequently wonder if lichens in their own home landscape is a sign of disease or decline.

Everyone seems so relieved to hear that the gray-green, paisley-like growth is, in fact, the sign of a healthy environment. There’s a reason you don’t see lichens on urban trees: They’re very sensitive to air pollutants.

There’s also a simple reason you don’t see lichens on young, healthy trees and shrubs. They can’t establish on plant tissue that’s still growing at a quick pace. Once a tree matures and its growth slows, lichens can grab hold.

Lichens aren’t single organisms, but composite structures made up of algae and fungi. Of the three main types of lichens, those seen on trees in general and BBG trees in particular are foliose lichens, which produce a flattened, leaf-like, lobed growth.

Colors vary between lichens species because of different combinations of fungal and algal components. And colors change through the season due to varying moisture levels. Unlike other plants, they don’t have vascular tissue to move nutrients and water. Instead, they simply absorb what they need from surrounding air and rain. During dry times, they often go dormant and appear gray, whereas moisture brings out the bluer or greener color of underlying algae.

Recent studies have found that lichens around the world, and specifically the algae that fuel them, are endangered by the predicted rate of climate change, which vastly outstrips the rate at which these algae have evolved in the past. It is estimated that lichens are the dominant vegetation on 7 percent of the Earth’s surface, where they are a source of sustenance for many species, so this has no small impact.

Keep watch this winter and early spring, whether you are shoveling snow or hiking your favorite trails, so you can pay special attention to your local lichens before the emerging foliage, buds and blooms take back their starring role.

Chris Ferrero, a gardening speaker, writer, consultant, and Cornell Master Gardener, serves as a volunteer tour guide here at BBG.

Help Our Garden Grow!

Your donation helps us to educate and inspire visitors of all ages on the art and science of gardening and the preservation of our environment.

All donations are 100 percent tax deductible.